If you look at the current pseudoscientific movement that has taken over the United States, you’ll notice a few oddities. They tend to really like ivermectin, which is a very useful drug when used for certain parasitic diseases, but also not a miracle cure of all ill health. There’s also a strong theme in all of the MAHA writing that Americans are less healthy than other countries, and doing much worse than they used to. This is generally attributed to a variety of food additives - that dreaded Red Dye 3 - but also to the fact that the US has been getting fatter for some time.

The thing is, if you look at the data closely, it doesn’t really support this belief. Type 2 diabetes is a great example*. The disease is directly caused by obesity, and you can largely reverse the symptoms by losing a lot of weight.

The number of people with diabetes has also been skyrocketing in the US for a long time. The CDC estimated in 1980 that 5.8 million US residents had diabetes. The most recent 2021 estimates suggest that this has increased to a whopping 38.4 million, with most of these cases being made up of Type 2 diabetes.

So why do I say that diabetes rates are falling? Well, it has to do with the ambiguity of the term “rates”, and also how these things are calculated.

Rates

The first issue we have to discuss is the different ways that we use the term rates. It’s a pretty ambiguous word, and there are several ways to interpret it. There are two important terms that you have to understand at the start here:

Incidence: the rate of new diagnoses of a disease in a population.

Prevalence: the rate of existing diagnoses of a disease in a population.

Both incidence and prevalence are usually measured at a point in time or in a specific time-frame. With diabetes, the incidence is the proportion of people who get a new diagnosis of the disease over, say, a year. Conversely, the prevalence is the rate most people generally think of first - the proportion of people in a population who have a disease at a point in time.

If you look at the crude prevalence of diabetes, it has increased from 2.5% in 1980 to around 11.3% in 2021. This is, of course, a huge jump, even if we don’t count the addition of undiagnosed cases of diabetes.

But incidence is a very different story. The 1980s CDC report unfortunately didn’t give exact incidence rates, but they did give crude incidence figures. In 1980, they estimated that 541k people were newly diagnosed with diabetes. In 2021, the CDC instead estimated that it was 1,211k, so just over double.

This is still an increase, but it’s not nearly as big. Prevalence of diabetes has increased by more than 4x. If you account for population growth, incidence has only increased by about 0.5x.

This gives us our first big insight into diabetes rates. The only way you can have prevalence rising much faster than incidence for a chronic disease that is never cured is if people are living longer after diagnosis. The only way to stop being counted as part of the prevalence figures once you’re diagnosed with diabetes is to die. So we can say with quite a bit of certainty that a large part of that increase in diabetes numbers is because the disease is much less fatal than it once was.

That brings us on to our next rate-related point - what about age? We know that age is very closely related to diabetes, and that the US population has on average aged by about a decade since 1980. Since being older drastically increases your risk of diabetes, it might be in part that the increase in prevalence is due to the aging population rather than other factors.

This is, in fact, entirely accurate. If you look at the age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes, the rate increased from 9.7% in 1999 to 14.3% in 2017 and has since plateaued:

It is still an increase, but it’s a drastically smaller one than the crude figures we started with. Obviously, it’s not quite the same time-period, but it still shows that age is a big factor in the increasing diabetes rates. For some context, obesity rates during this period increased by about 50%.

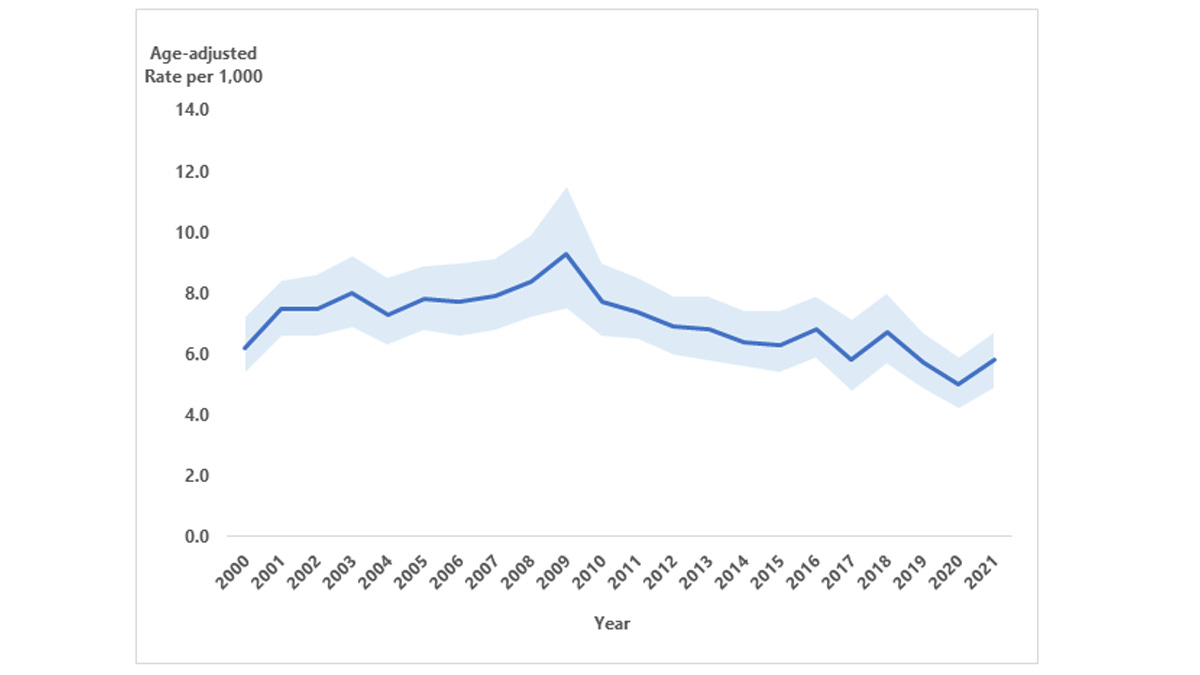

But then you look at incidence, and it’s an even more interesting picture. Once you adjust for age, the proportion of people with newly-diagnosed diabetes has been falling in the US since at least 2009:

So despite skyrocketing obesity rates, the likelihood that a person will be diagnosed with diabetes in the US is currently the lowest it’s been since the early 90s. The rate is currently 5.9 new diagnoses per 1,000 people, which is still higher than the rate 3 per 1,000 from 1983, but quite low and has been getting better for over a decade.

Complexity

I want to make it clear that this does not mean that obesity and diabetes are unrelated. Some portion of the rise in cases of diabetes is obviously caused by the massive increase in obesity.

We also know that losing weight is a very effective treatment for Type 2 Diabetes. If you can get people to lose 10-15% of their body weight they usually reverse their diabetes markers although it’s debated whether this means that the disease is gone or if the underlying damage caused by diabetes is still an issue.

That being said, there’s a huge misunderstanding about the status of diabetes and how this relates to chronic disease. Most of the increase in diabetes rates since the 80s in the US is likely attributable to older age and better survival. Older people are more likely to get diabetes, and people with diabetes live much longer lives in 2025 than in 1980.

There’s also another factor I haven’t touched on much here - improvements in diagnosis - which have had a big influence on these diabetes rates. Somewhere in the region of 50% of the increase between 1980 and 1999 is probably due to moving from onerous glucose tolerance tests, which take hours to do and are quite unpleasant, to much easier fasting glucose tests. The fasting glucose threshold was also lowered in the late 80s, which likely lead to millions of Americans being diagnosed with diabetes shortly after who would not have been considered to have the disease in 1980.

Obesity has certainly played its part, but to a large extent the increasing number of people with diabetes is a sign of health getting better. In the 80s there were a small handful of drugs available to treat Type 2 diabetes - now we’ve got dozens. GLP-1s like Ozempic and Mounjaro not only improve blood sugars, they reduce the risk of heart disease and kidney disease long-term. SGLT2is like Invokana have a similar range of benefits.

None of this contradicts the fact that more people getting diabetes is a strain on the healthcare system and generally not great, but some of the big causes of that strain are people getting older - i.e. not dying young - and getting treated better.

It’s also important to understand that whether things are getting better or worse in terms of diabetes in the US is very much dependent on which metrics you choose to use. The best answer is that diabetes is complex and mixed, but if you just pick a single statistic you can say almost whatever you want. If you compare the crude number of people with diabetes between 1980 and 2021 it seems like a terrifying increase - if you instead look at age-adjusted incidence for the last 20 years it looks like we’ve almost solved the diabetes problem already.

The statements “more people have diabetes in the US than ever before” and “fewer people are getting diabetes than in the 90s” are both true and both misleading.

The title of this piece shows precisely this issue. It’s true that the rate - the incidence rate - of diabetes has been falling in the US for over a decade. If I had only reported that rate, I could give the misleading impression that diabetes isn’t an issue any more.

It’s not that chronic disease isn’t a problem. It’s that chronic disease is a complex problem that has many causes and no easy solutions.

*Note: I’m going to talk pretty much exclusively about T2DM here. There are some interesting parts to the Type 1 story as well, but it contributes a very small % of total diabetes rates.

As usual, I appreciate your thoughtful approach to explaining statistics and study outcomes in science articles that have to do with issues that are controversial in our current situation. We do need thoughtful ways to prevent and treat type 2 diabetes. And because some of what makes it a challenging health care problem have to do with social and psychological aspects of our humanity, like some people eating a lot of sugary treats in part to deal with depression, it isn't 100% solvable by physical sciences.

I read the whole piece and was about to call you out on the title (which felt fairly click-baity). Until you yourself pointed out that it was indeed biased and an example of how any one stat can be tweaked to tell any story you want.

My bigger concern today is how many of the policies being put in place and cuts being made are going to disproportionately impact higher risk populations. I anticipate a lot of even the positive-looking stats to turn negative in the coming years as a result of it. 😞