Kimchi is the name that, outside of Korea, is generally given to a dish made of spicy fermented cabbage - in Korea it refers to a wide variety of pickled and otherwise preserved vegetables. Much like sauerkraut and similar dishes, Kimchi is an acquired taste, but once you love it, you love it, and can’t do without.

And, according to a swathe of recent headlines, kimchi is also a fantastic tool for weight loss. Based on the headlines, eating up to three servings of kimchi a day is a great way to drop those pesky pounds and keep yourself as light as possible using nothing but a “fermented superfood”.

Unfortunately for those of us who love kimchi, the reality is much less hopeful than the headlines. While kimchi is a pretty healthy thing to eat, there’s no good evidence that just eating the stuff will help you lose weight. The recent headlines are - hilariously - the work of Big Kimchi, trying to sell you more of the fermented cabbage than you’d otherwise eat.

Let’s look at the science.

The Science

The study that has everyone so excited is a new epidemiological paper published in BMJ Open, an offshoot of the more well-known British Medical Journal. It’s a very basic cross-sectional paper, where the authors took a large database of South Korean people who’d given information on both their diet and other health factors between 2004-2013, and analyzed the data from this study to see whether there was an association between the likelihood of someone reporting that they were obses and their kimchi consumption. The term cross-sectional here means that the authors only have a single survey response from each participant - they couldn’t track people over time.

Straight off the bat, that means that this study tells us little about causal relationships. You can’t really say if kimchi is causing people to gain/lose weight if all you’ve got is a single time point - you can just say that people who say they eat kimchi more/less are also more/less likely to be obese.

What the authors did with this dataset was very standard. They divided people up by how much kimchi they reported eating a day - as well as dividing kimchi up into two separate types of kimchi, because this is Korea - and then looked at the risk of obesity in a statistical model that corrected for common confounding factors. They also defined obesity both by BMI and by waist circumference, two very standard measures of how fat people are.

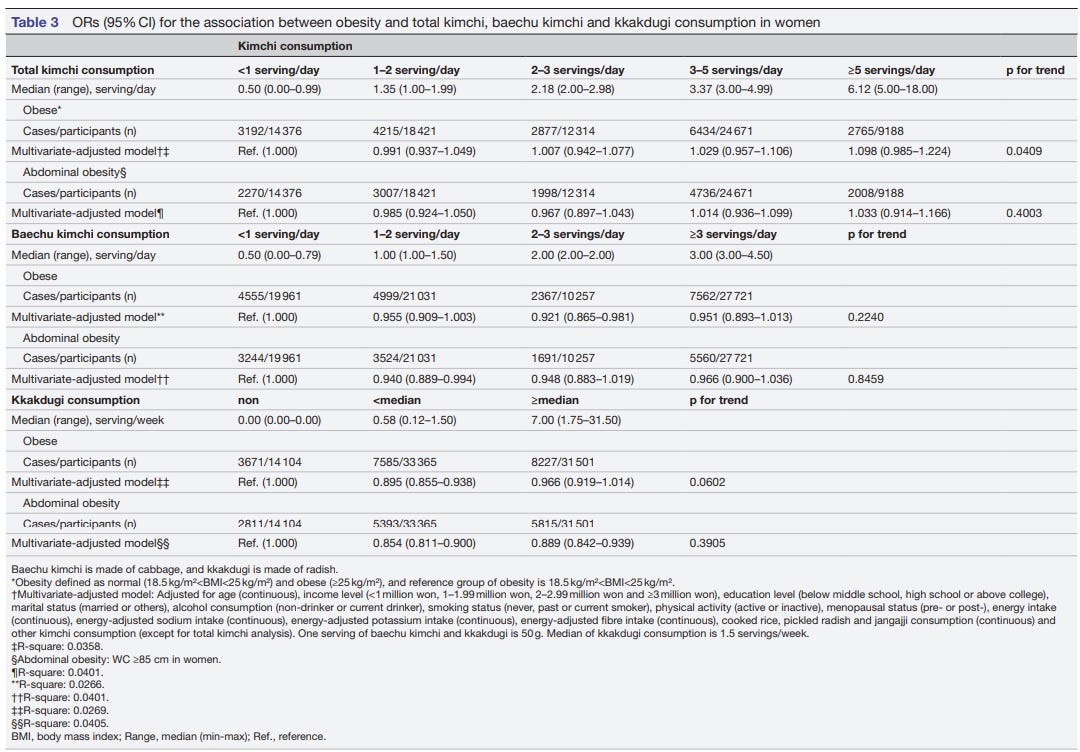

If you read the conclusions from the authors in the study, what they report finding is that there was a reduction in the risk of obesity for men who ate 1-3 servings of kimchi per day, compared to men who ate none. There were also some reductions in specific subgroups of kimchi eaters, such as women who ate more than the median intake of radish kimchi.

However, when I looked at the actual data that the study presents, it turns out that this is enormously misleading. Here are the tables of results from the statistical models in the study:

These may look like gobbledegook, but they’re very enlightening if you know how to read statistical results. Firstly, if you look at the male table (table 2), you can see that there’s barely a relationship there. There’s no linear association between kimchi intake and obesity, and at best there are a handful of places where men who eat very specific amounts of kimchi may be slightly less likely to be obese than men who eat none at all.

But the female table is really startling. The first line there shows that there is a straightforward linear association between kimchi and risk of obesity in their multivariate model. In other words, for women, eating more kimchi was associated with a HIGHER risk of obesity in this study.

This is precisely the opposite of what the news reports and indeed the study authors themselves have said. While the association here is a bit dubious anyway - the study design simply isn’t strong enough for us to draw any useful conclusions about kimchi and weight - it still shows that, at least for women, more kimchi meant a higher weight, not lower.

It’s hard to describe this as anything other than cherry-picking. The authors have picked out one or two associations that make kimchi look good, and ignored the ones that make kimchi look bad. Why did the authors misrepresent their own findings?

Promoting Kimchi

As someone who checks scientific facts professionally, I try not to litigate intentions. It’s impossible to tell, from reading a study, why people have done the things that they have done.

However, in this case, there’s a useful piece of information that’s missing from most of the reporting. The media pieces are all based on a press release from the BMJ, which said that the study was funded by the South Korean government. However, what everyone failed to notice was that the study was funded by a very specific part of the government - the World Institute for Kimchi, a national organization that exists to promote the use of kimchi and boost the kimchi industry to help the Korean economy. Two of the authors work for this institute.

It’s not hard to see how people working for the World Institute of Kimchi might write a paper that presented kimchi in a good light, even if the evidence didn’t show such benefits. The same institute has been behind a large number of scientific studies, for example this recent low-quality randomized trial comparing three types of kimchi for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. They regularly fund research from Korean researchers that has noticeable problems, and also manages to find that kimchi is good for your health.

Yes, this most recent paper comes to you from Big Kimchi. They join Big Blueberry, Big Pasta, and even Big Walnut as yet another group funding scientific research to promote a specific food or food group. Frankly, it’s hard to trust any research that comes from a food industry group that’s explicitly set up to promote that product, especially because such research tends to be very low-quality.

My advice is to eat kimchi if you like it, but don’t expect miracles. Like most fermented vegetables, it’s low-calorie and has a bunch of nutrients, so you can eat essentially as much of it as you want to, but it probably isn’t going to magically make you lose weight nor improve your health in other ways.