The Future Risk Of Long COVID

What are we likely to see with the risk of Long COVID into the future?

Minor update - it was pointed out to me that the upper bound of seasonal non-COVID coronaviruses incidence is likely higher, so I’ve updated the text to reflect this.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has progressed, one thing has become ever more clear - the individual risk from the disease is dropping over time. When I worked on the death rate in 2020, looking at a huge range of research to reliably estimate how many people died per infection, the numbers were scarily high. By 2023, a reasonable estimate is that the risk from an acute COVID-19 infection has dropped by a factor of at least 10, which puts the coronavirus into the same range of lethality as flu and similar seasonal problems.

That’s nothing short of miraculous.

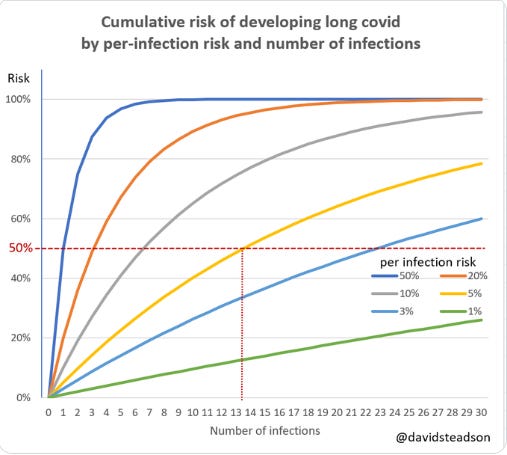

But COVID-19 doesn’t just cause acute outcomes, and people are also worried about the long-term symptoms that we’ve termed Long COVID. People are still concerned that, despite the dramatic drops in COVID-19 severity, there will be an ongoing massive risk of Long COVID well into the future. This is perhaps best exemplified by this graph that I have seen shared around looking at the cumulative risk of developing Long COVID:

This seems to represent a lot of the fears that people have - that despite the reduction in COVID-19 lethality, we will still all eventually get very sick. I thought I’d explain why this graph is wrong, and why even though COVID-19 and Long COVID will both be problems forever, the risk of having long-term symptoms in the future is most likely to be very low.

This doesn’t mean that Long COVID has fallen off the radar entirely - it’s still a serious concern that some people are suffering from years after having an infection. But it does mean that the future is far more rosy at a population level than things like the graph above might have led you to believe.

Future Risk

I’ve written before about your current risk of Long COVID. Various data sources indicate similar results, which is that the risk was somewhere around 10% per infection in 2020, it decreased to around 3% by the end of 2021, and dropped to somewhere in the region of 1-2% by 2023.

But what of the future? The graph above shows a monotonically increasing risk of Long COVID per infection, with different rates of increase. This basically means that the graph assumes that each infection confers the same risk of getting long-term symptoms, and the implication is that most people will eventually have many COVID-19 infections. This is extremely misleading for two main reasons:

Infection risk is decreasing over time. This is a fairly well-proven fact. If you look at the Office for National Statistics in the UK, with their excellent COVID-19 infection survey, the proportion of the population being infected peaked during Omicron in 2022 and has declined since then. Unfortunately, the ONS stopped collecting data for this survey in March 2023, but the data up until that point suggested that there were an average of just over 1 infection per person in 2022, and that this had declined significantly even by the start of 2023. The ONS has started collecting a new dataset with the UKHSA, called the Winter Coronavirus Infection Survey, which uses lateral flow tests instead of PCR testing to determine rates of COVID-19. While this will always produce a slightly lower result, due to some missed cases, the initial results of the Winter Coronavirus Infection Survey suggest that around 1% of people had COVID-19 in the UK in the last week of November 2023, compared to about double that number from a similar time last year.

The risk per infection of getting Long COVID is declining dramatically. The ONS estimated that the rate of Long COVID was reduced by about 30% after a second infection when compared to a first. A new study from Sweden suggests that the risk of Long COVID after a wild type COVID-19 infection was nearly 10x higher than the risk for Omicron. Another study from the extremely robust REACT dataset in England estimated a similarly massive reduction in risk of Long COVID between 2020 and 2022. Current best evidence suggests that vaccination also reduces the risk of Long COVID by up to 73%. It’s hard to say precisely how big the reduction is per additional infection, because measuring that difference is complex, but we can say with a great deal of certainty that the incidence of Long COVID has dropped by at least half every year since 2020.

If you put these two well-demonstrated facts together, you get a situation where you are less likely to be infected every year, and each infection is less likely to give you Long COVID.

Let’s think about this based on the evidence to date. In 2022, the highest risk year for catching COVID-19, there were about 1.3 infections per person in the UK, based on ONS data. It’s hard to know exactly how many people have been infected in 2023, but UK data on hospitalizations and deaths suggest that the figure has fallen by at least half. As I noted above, the rate of infections looks like it’s about halved based on ONS data as well. That’s still quite high, but given the epidemiology of other coronaviruses - which infected 1-15% of the population each year prior to COVID-19 - we would expect the rate to drop even further.

In context, this makes the graph above even more problematic. If we assume that people are going to get COVID-19 at a very high rate forever - say, once every two years - then it would take 60 years in total to experience 30 infections. If the rate of infections decreases to something that is more akin to endemic, seasonal coronaviruses, then most people will never be infected more than three or four times.

If you were to make a realistic estimate starting in 2022, with 100% of people having an infection in the first year and then a falling proportion thereafter, and 10% of people who are infected experiencing Long COVID with that number also falling over time, the graph would look a bit more like this:

Obviously, there are a lot of assumptions here, but they are not unrealistic. The graph plateaus at about 15% or 5% depending on whether people were vaccinated in 2022. Interestingly, this projection is fairly consistent with the CDC’s Household Pulse survey, which estimates that around 15% of US adults report ever experiencing long-term symptoms associated with COVID-19, a number that hasn’t increased in 2023.

All Models Are Wrong

There’s an old statistical adage that’s helpful to remember in these situations - all models are wrong; some models are useful. Neither the graph I’ve made nor the original one are likely to accurately reflect the truth.

However, we can think about what the risk looks like as time moves on, and we’re already seeing strong evidence that it’s more like a plateau than a steadily increasing tsunami. For example, there was a big spike in people off work due to sickness around the time of the massive Omicron waves in 2022, but this number has since fallen dramatically to more normal levels. While the rate of people out of work in the UK has been increasing since 2019, and reported disability has been increasing since 2011, in other countries applications for disability services have plateaued or even fallen since the start of the pandemic. Estimates attempting to assess the causal impact of Long COVID on additional disability have shown that only a very small proportion of people who report being out of work do so because of Long COVID. We certainly aren’t seeing a huge wave of additional disability since the onset of COVID-19 that we might expect if the majority of the population was getting severe Long COVID.

All of the evidence shows that the risk of Long COVID was highest in the early pandemic, and has fallen dramatically since then. The data suggests that the peak of Long COVID has long since passed, and the risk will probably continue to fall as time goes on. Of course, this is slightly complex when you look at entire lifetimes - for a 40-year old today, their risk of Long COVID and other severe COVID-19 outcomes will rise again as they age and will probably be quite high once they hit 85 - but at least in the next decade or two we’ve got a decent idea of what’s likely to happen.

This doesn’t mean that Long COVID is no longer an issue. There are many people who got sick in 2020 who are still suffering terribly years later. Even if the rate of Long COVID is now low, and falling, there are still enough infections that the number of people experiencing new cases of Long COVID will be at least in the hundreds of thousands in the US alone for years to come. But it is very reassuring to see that the worst impacts of the pandemic, even when it comes to Long COVID, are almost certainly well behind us in 2023.