The Terrifying Problem Of Fraud In Women's Health

A scientific issue impacting pretty much every person with a vagina.

This week, I attended and presented at the International Research Integrity Conference. As with most conferences, it was a mix of sessions, with fascinating plenaries, student posters, a workshop, and more. It was all fueled by our insatiable curiosity and an endless stream of coffee-filled carafes.

In most respects, a very standard conference. This one, however, was different to most, because of the subject matter: fraud.

Now, I use the term fraud a bit glibly there. Technically, what we’re always talking about is untrustworthy or unreliable research. It is hard for someone looking at a PDF of a study to make a judgement call about what the authors intended to do. Fraud, after all, is deliberate manipulation, and in many cases where you find a problematic piece of research it’s impossible to distinguish intentional fabrication from incompetence or even other problems that can impact scientific research. There are also lots of more minor mistakes that may be more innocent that nevertheless make research useless for medical decision-making.

Regardless, in simple terms we were talking about scientific research that is either made up or might as well be—hence the term untrustworthy. It’s a much bigger problem than most people realize. And there’s one place in particular that seems to be taking everyone by surprise—women’s health.

Let’s look at the enormous issue of fraudulent research in obstetrics and gynecology, and how it has undermined decades of medical recommendations. If you have a vagina, or know someone who does, chances are that you’ve been impacted by studies that may never have happened at all.

Problematic Studies

When you’re in the thick of something, it’s hard to realize how niche that issue may be. Most of the people that I talk to on a daily basis have a decent understanding that there are lots of untrustworthy studies out there, and that women’s health is particularly bad.

But the rest of the world—including most of the people who work on women’s health in their daily lives—haven’t been inculcated into the murky world of scientific misconduct in the same way that I have. I’ve literally been told by a researcher that the data for their trial was unavailable because they lost their laptop, shortly after proving that the numbers in their published trial were mathematically impossible.

That sort of thing tends to make you a touch jaded.

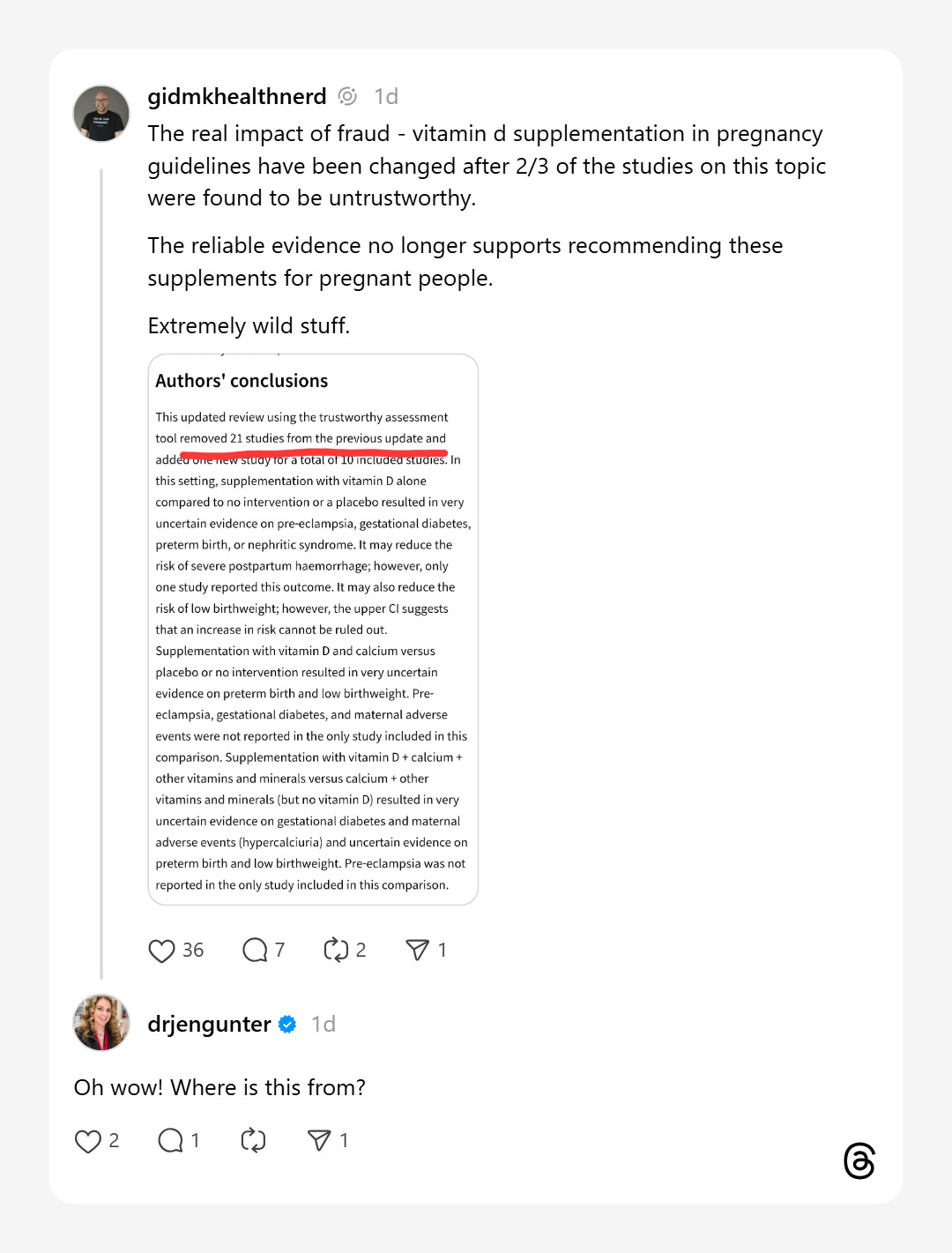

So when I posted on Threads about one of the many incidents of untrustworthy research impacting people’s lives, I was a little bit surprised at the responses. For example, the wonderful

:The study that I was citing in that example is here. It’s a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials from the Cochrane Collaboration looking at vitamin D supplementation for pregnancy. This is basically the highest standard of evidence that exists in the medical sphere—Cochrane reviews are relied upon by most national and international agencies to set guidelines that doctors, nurses, midwives, and everyone else relies on to treat patients.

The 2019 review had some very strong findings. I think it’s worth quoting the conclusions in full here:

“Supplementing pregnant women with vitamin D alone probably reduces the risk of pre‐eclampsia, gestational diabetes, low birthweight and may reduce the risk of severe postpartum haemorrhage. It may make little or no difference in the risk of having a preterm birth < 37 weeks’ gestation. Supplementing pregnant women with vitamin D and calcium probably reduces the risk of pre‐eclampsia but may increase the risk of preterm births < 37 weeks (these findings warrant further research). Supplementing pregnant women with vitamin D and other nutrients may make little or no difference in the risk of preterm birth < 37 weeks’ gestation or low birthweight (less than 2500 g). Additional rigorous high quality and larger randomised trials are required to evaluate the effects of vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy, particularly in relation to the risk of maternal adverse events.”

The findings are impressively positive. There are some potential risks, but overall the reduction in negative health outcomes from this review are sufficient justification for telling every pregnant person to take a vitamin D supplement during their pregnancy.

But there was a problem. The review had included a number of studies by an author group who are rather notorious in the scientific integrity world. The team has racked up nearly 30 retractions and a further 50 or so expressions of concern so far, putting them in the running to join the Retraction Watch leaderboard of the most retracted researchers of all time.

I commented on the review in 2023 pointing out this issue. I found the problem when I was looking into recommendations for supplements during my wife’s pregnancy. It was no one’s fault—the review was published shortly before the concerns about these authors came to light—but nevertheless it substantially undermined the findings.

Cochrane reviews are the gold standard in medical care for a reason. Updating and redoing an entire systematic review and meta-analysis takes an enormous amount of time. Adding an additional step to that work is even harder. And yet, the authors set about doing just that. About a year after my comment, the review was updated with a new version. The team had conducted careful checks of integrity for all of the included studies, and excluded papers which were untrustworthy for whatever reason. I’m going to again put the full conclusions here because I think the comparison is…stark (bolding added for emphasis):

“This updated review using the trustworthy assessment tool removed 21 studies from the previous update and added one new study for a total of 10 included studies. In this setting, supplementation with vitamin D alone compared to no intervention or a placebo resulted in very uncertain evidence on pre‐eclampsia, gestational diabetes, preterm birth, or nephritic syndrome. It may reduce the risk of severe postpartum haemorrhage; however, only one study reported this outcome. It may also reduce the risk of low birthweight; however, the upper CI suggests that an increase in risk cannot be ruled out. Supplementation with vitamin D and calcium versus placebo or no intervention resulted in very uncertain evidence on preterm birth and low birthweight. Pre‐eclampsia, gestational diabetes, and maternal adverse events were not reported in the only study included in this comparison. Supplementation with vitamin D + calcium + other vitamins and minerals versus calcium + other vitamins and minerals (but no vitamin D) resulted in very uncertain evidence on gestational diabetes and maternal adverse events (hypercalciuria) and uncertain evidence on preterm birth and low birthweight. Pre‐eclampsia was not reported in the only study included in this comparison. All findings warrant further research. Additional rigorous, high‐quality, and larger randomised trials are required to evaluate the effects of vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy, particularly in relation to the risk of maternal adverse events.”

We’ve gone from a treatment that was almost overwhelmingly recommended because it reduced a whole range of bad outcomes to one that is now uncertain and potentially harmful. All because of trustworthiness checks to see if the studies that the review had included were worth relying on.

And these checks are not just arbitrary. In at least one case, a study included in the 2019 review had since been retracted due to “concerns regarding the validity of participant data in this study, the timing of ethical approval and trial registration, the statistical analysis, and citation to another article reporting on this trial.” Several others had received editorial expressions of concern. The papers used in the initial review were, for whatever reason, highly untrustworthy.

This is not the only review that is getting an update. There has been a massive effort in the Cochrane Collaboration over the last few years to update many of their papers relating to pregnancy and childbirth. This review on steroids prior to planned cesareans was updated with 3/4 of the trials removed due to trustworthiness issues. Another review looking at interventions to treat fetal growth restriction—when fetuses stop growing in the womb—updated its methods halfway through and ended up removing half of all the studies that they found due to concerns over trustworthiness.

A recent update to the review of tranexamic acid (TXA) to prevent bleeding after birth excluded all of the studies included in the initial review due to serious issues with trustworthiness. The conclusions changed from a very favorable recommendation to being entirely uncertain about benefit and warning about harms. The updated conclusion reads:

“Those making decisions about routine administration of prophylactic TXA for all women having vaginal births should consider that current evidence does not show a benefit of TXA for blood loss outcomes and related morbidity, and the evidence is very uncertain about serious adverse events.”

The current guidance from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends the use of TXA when other treatments for blood loss are unsuccessful. The guidance does not strictly recommend prophylactic use, but it notes that this is an option. It was published in 2017, and cites the 2015 review which was just updated.

If these were the only reviews, it would be one thing. Bad, but manageable. But this is just the start. There are hundreds of papers out there which almost certainly have similar flaws to these ones which are still being worked on. Professor Ben Mol, who is the driving force behind many of the retractions of untrustworthy studies in the obstetric literature, has reported well over 1,000 papers so far and there are many more out there. Hundreds of these papers have been retracted.

Your Healthcare

There are two major problems with this situation. The first is that Cochrane reviews use a lot of untrustworthy studies in them, and that has caused people to receive what may have been entirely useless or even harmful treatments.

But that problem is being fixed. Cochrane is aware of the problem, and they’re doing a lot of work to mitigate it so that their reviews don’t harm people in the future. Cochrane reviews are also robust enough that many of their conclusions won’t change, because they excluded untrustworthy data already for other reasons.

The thing is, not everyone uses Cochrane reviews. They haven’t done a review on every question, and sometimes they don’t give particularly useful advice. The most common finding for a Cochrane review is that there is not enough good data to provide medical advice, which can be frustrating for doctors who have to make medical decisions regardless of the quality of the data.

There are also many hundreds of thousands of non-Cochrane reviews out there. These are less impactful, but many of them still make their way into guidelines and are used in treatment. Most medical societies, for example, commission their own systematic reviews whenever they have a treatment question that they can’t find an answer to in the literature.

These reviews aren’t being checked for trustworthiness. The idea of screening papers for potential trust issues isn’t even on most people’s radar. There’s a good reason that Cochrane reviews are the gold standard and everyone else is second-best.

The problem isn’t confined to women’s health. The field of supplements—vitamins, herbs, etc—also seems to be plagued by dodgy research. The field of aromatherapy seems to be particularly bad as well. Anesthetics has also had some of the most prolific admitted frauds in scientific history.

But when it comes to direct impact, the issues in obstetrics and gynaecology are probably the most viscerally problematic. It’s hard to imagine a bigger scientific problem than dodgy studies that doctors are using to decide on treatments for someone who is bleeding heavily after giving birth.

Unfortunately, I have no straightforward, easy solution here. This is a systemic problem that we are only beginning to address. Science is built on trust, and that has for some time allowed bad actors to do dodgy things that are even now making us less safe.

The only thing I can say is that more pressure is needed. If this was any other area of work, people would be banging on the doors of journals and publishers with pitchforks. The powerful people who decide on the direction of academic focus are mostly naive or uninterested in the problem of misconduct. We cannot leave it to the slow and tedious pace of academic correction when people’s lives are hanging in the balance.