The Cass Review Into Gender Identity Services for Children - Part 1

Has there been an exponential increase in young people with gender dysphoria?

This is part 1 of my series looking at the Cass review into gender identity services for children in the UK. You can find the other parts here (I will update as I add sections):

In case you’ve missed my earlier pieces, here’s a brief summary of the Cass review:

Large-scale review into the evidence for gender identity services for kids in the UK.

Took about 3.5 years, covered a wide range of topics. Overall recommended that most medical treatments be abandoned for children, but that the government should run RCTs looking at whether these treatments (hormones and puberty blockers) have benefits.

Very controversial.

One of the main arguments that the Cass review has made is that there has been a dramatic and hard-to-explain increase in the number of children who identify as transgender and attend UK clinics with gender dysphoria seeking help. In a number of places, the review describes this increase as “exponential”, and notes that it appears to have been accelerating in recent years:

“From 2014 referral rates to GIDS [the UK Gender Identity Development Service] began to increase at an exponential rate, with the majority of referrals being birth-registered females presenting in early teenage years” (page 85, bolding added for emphasis)

“In the sample drawn from CPRD data (Figures 13 & 14) (Appendix 5), recorded prevalence of gender dysphoria in people aged 18 and under increased over 100-fold between 2009 and 2021. This increase occurred in two phases; a gradual increase between 2009 and 2014, followed by an acceleration from 2015 onwards.” (page 87, bolding added for emphasis)

This is a central part of the argument of the review. The authors say that this increase is far too big to be caused by social acceptance of trans people, and therefore there must be some form of pernicious influence such as social media, mental health problems, or some other issue causing kids to become trans at increasing rates. For example, later in the review the authors specifically argue that the “increase in numbers within a 5-year timeframe is very much faster than would be expected”

They are arguing that the increase isn’t just big - it’s so big that it cannot be natural. It’s not even clear that the review is using exponential in a literal mathematical sense - it’s a bit like when right-wing commentators call any rise in immigration an exponential increase. It’s not that the numbers follow an exact exponential gradient, it’s that there’s a massive rise that should terrify us all.

But if you look at the actual data in the reports that the review is discussing, not only is the increase not exponential, it’s not actually that surprising. When you consider the context, it seems much more likely that this increase in children referred to gender identity services is exactly what we’d expect.

The Data

The review uses two primary sources of data for its discussion about the increase in gender dysphoria and transgender identity in young people - one of the systematic reviews from the University of York, which looked at studies on the epidemiology of gender identity, and an epidemiological study into the UK gender identity services.

The systematic review is an interesting paper. As with all systematic reviews, the authors aimed to capture all studies looking at a particular question. In this case, they searched for every published scientific estimate looking at the number and rate of children attending gender services over time, the assigned sex of those children, and co-occurring mental health issues such as eating disorders and depression. As with all the reviews done for the Cass review, this one looks to be a high-quality piece of work done by experienced reviewers.

The review identified a total of 131 studies. Because they were simple descriptive papers, they were not rated for bias or reliability (we’ll talk about that later in the series). The authors made three main conclusions from these studies:

There has been a “twofold to threefold increase” in the number of children being referred to gender services that provide medications and other treatments in the last two decades or so.

The ratio of trans girls* to trans boys has changed - in the 90s and 00s, there were more trans girls, but as time has gone on many of the countries have seen a bigger number of trans boys coming in to these services.

There are high rates of co-occurring mental health conditions in this population, with many trans kids who are seen by gender identity clinics having depression, anxiety, or another mental health problem. Rates of suicidality - children reporting thinking about suicide - were also high, as were rates of autism and ADHD.

The second two points are fairly well-proven facts that I doubt anyone would argue with. In terms of the increase in presentations, however, the authors seem to have made some inaccurate statements. Specifically, they say that:

“Around 5–6 years into the data presented by year in the individual studies there is a sharp increase (twofold to threefold) in referral numbers across all countries except the Netherlands which started to increase in 2011 and Denmark which only had 2 years of data.” (Taylor et al, 2024)

But as you can see from the graph below, which is taken from a reproduction of the study included in the Cass review, this isn’t entirely true. There were several countries with no/minimal increase in referrals in this time, including Israel, Scotland, and Belgium. The Netherlands had several inflection points across the last two decades, including a drastic 6x increase between 2001 and 2003. There is no clear timepoint where countries saw an increase, and it’s hard to see a specific trend. Certainly, most countries did see more referrals, but this doesn’t look much (or at all) like the “exponential” rise the Cass review paints it to be.

The second major source of data for the Cass review on this question is an epidemiological study that the University of York conducted looking into children in the UK. They looked at the two main ways that we identify numbers of transgender children using clinical record systems:

Referrals to gender specialist services.

Codes of gender dysphoria in clinical records.

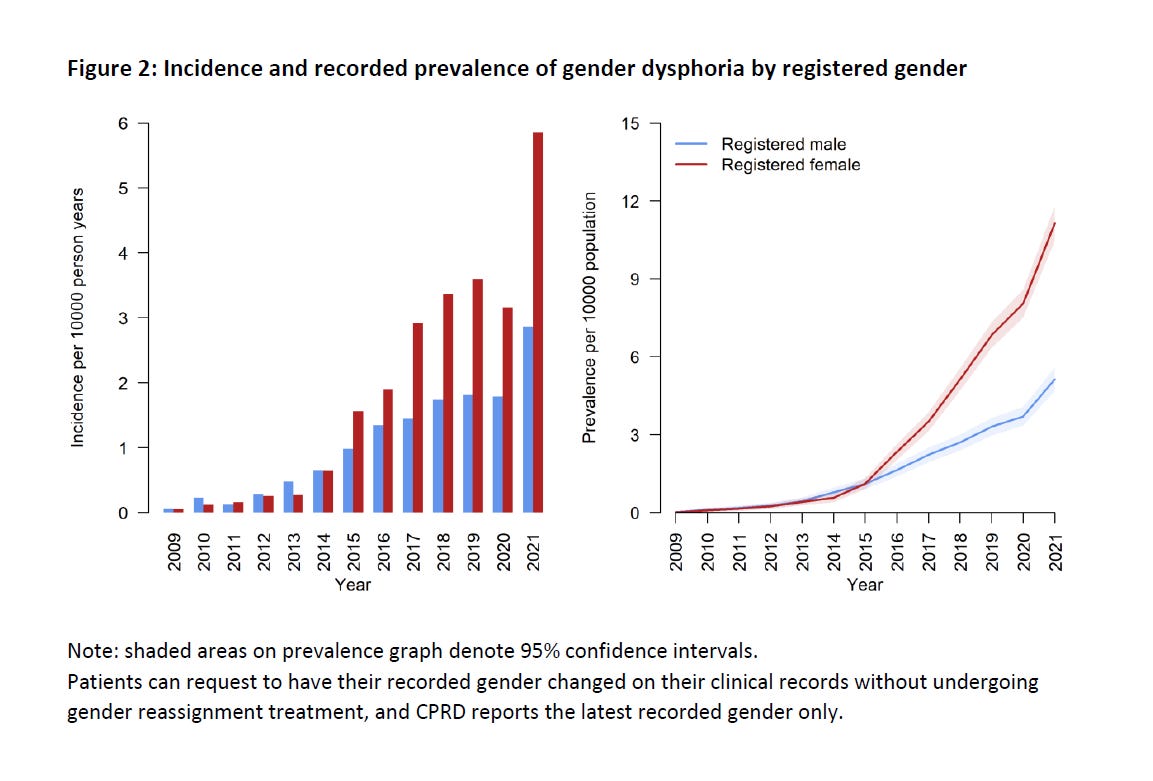

In the review, the results are positioned as a minor increase from 2009-2014, followed by the “exponential” rise from 2015 onwards. They show this in the graphs below:

If you squint, you might see the issue here. It’s important to be careful with numbers like these. I extracted the data using an online tool, and then replotted the incidence - i.e. new diagnoses of gender dysphoria, the left graph - using a log scale by year. Here’s what that looks like:

On a log scale (this is base 10), an exponential increase shows up as a straight line. What you can see from these graphs is that the data shows essentially the opposite to the trend proposed by the Cass review. There was an exponential increase, but it started in 2009. By 2015/16, the increase had become mostly linear, and was even plateauing before the pandemic. The authors note that the pandemic years are a bit misleading - 2020 had a fairly big drop in cases, and 2021 a proportional increase - so if we look only at 2016-2019 it seems like the rate had pretty much stabilized.

This may seem finicky, but it’s really important. Rather than being overrun by trans kids, we are seeing what looks like a plateau in cases. There was a drastic rise when services first became available - particularly in the late 00s and early 10s - but towards the end of the decade this rise slows down substantially.

What’s interesting is that this time period saw a huge upheaval in the diagnosis of gender-related issues. Specifically, in May 2013 the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association, which is the go-to bible for mental health diagnoses, changed their diagnostic criteria. In the DSM-4, gender issues fell mostly under a diagnosis of Gender Identity Disorder, a fairly strict diagnosis that required numerous indicators of gender-related distress. This was substantially broadened in 2013 with the switch to Gender Dysphoria. For example, Gender Identity Disorder largely excluded non-binary people, while Gender Dysphoria has specific language to include non-binary and other gender identities.

If you go back to the figures, there’s clearly a huge increase in gender dysphoria codes that occurs around 2013. Indeed, the incidence for both boys and girls more than doubles between 2013 and 2015 alone.

Increasing, Not Exponentially

So, we know there’s an increase in people with gender dysphoria by any measure. Over the last 20 years, we can see everything from dramatic increases to far more modest booms depending on the time, place, and method of estimation. In the UK, there appears to be an exponential increase in both referrals to the gender identity services and gender dysphoria diagnoses that was accelerating until 2015, but then leveled off before the pandemic.

The Cass review does discuss possible reasons for these increases, including biological and psychosocial causes. For biological influences on transgender identity, the authors note that these are a) highly speculative and b) haven’t changed in the last few decades, so it’s likely that psychosocial factors explain the increase.

Specifically, these five factors:

“Societal acceptance: The proposition is that greater acceptance of transgender

identities has allowed young people to come out more easily and the increased

numbers now reflects the true prevalence of gender incongruence within society.”

“Changes in concepts of gender and sexuality: These might include a change

in expressions of sexuality versus gender and a wider spectrum of expression

(for example, non-binary and other gender identities that are more common

presentations in birth-registered females).”

“Manifestation of broader mental health challenges: For example, in the same way that distress can manifest through eating disorders or depression, it could also show itself through gender-related distress.”

“Peer and socio-cultural influence: For example, the influence of media and

changing generational perceptions. This is potentially the most contested explanation, with the term ‘social contagion’ causing particular distress to some in the trans community.”

“Availability of puberty blockers: The change in the trajectory of the referral curve across many countries coincided with the implementation of the Dutch approach, starting first in the Netherlands and then similarly adopted in other countries.”

First, they soundly reject societal acceptance as a cause of the “overall phenomenon”. They argue that the exponential increase in numbers within the last 5 years, the rapid increase in numbers across all Western populations, the increase in trans boys, the differences between generations (i.e. Gen Z vs Millennials), and the increase in other mental health problems during this time mean that societal acceptance cannot be the primary cause of this change.

But none of these arguments make much sense. The “exponential” increase is more like a plateau, at least in the UK, in the last 5 years. The “rapid increase in numbers…across Western populations” is actually an inconsistent increase with some countries seeing no increase at all. The increase in trans boys is just a weird non-sequitur - this could of course come about through changes to how society sees trans people.

The “sharp differences” by generation is a bizarre point, because the review bases this analysis on the pop psychology book Generations: The real differences between gen Z, millennials, gen X, boomers, and silents - and what they mean for America’s future. It’s the first time I’ve seen a pop psych book used as a source for decisions in a government document. As to the increase in mental health issues in people presenting to gender clinics, the review does not expound on why this would be problematic under the societal acceptance model.

The review then goes on to argue that all of the following points - changes in gender/sexuality, mental health challenges, peer influence, and availability of puberty blockers - have likely influenced the increasing number of trans youth to some degree. While all of these issues are discussed with some uncertainty, none of them are rejected out of hand in the same way that societal acceptance is. Indeed, the review implies that at least some measure of gender dysphoria is caused by mental ill health:

“The association is likely to be complex and bidirectional - that is, in some individuals, preceding mental ill health (such as anxiety, depression, OCD, eating disorders), may result in uncertainty around gender identity and therefore contribute to a presentation of gender related distress. In such circumstances, treating the mental health disorder and strengthening an individual’s sense of self may help to address some issues relating to gender identity.” (page 119)

The review also implies that social media and online influencers have likely contributed to the rise in trans identification:

“More specifically, gender-questioning young people and their parents have spoken to the Review about online information that describes normal adolescent discomfort as a possible sign of being trans and that particular influencers have had a substantial impact on their child’s beliefs and understanding of their gender.” (page 120)

Overall, the impression from the review is that the “exponential” increase in trans identification and gender dysphoria is definitely not due to societal acceptance. Instead, likely explanations include influencers convincing kids that they are trans, mental health issues causing more people to have gender dysphoria, some odd speculation about same-sex attraction being a cause of gender confusion, and some further speculation about broader access to puberty blockers around 2014 in the UK causing more children to seek the intervention.

There are two problems here. Firstly, the review has discarded the most obvious explanation out of hand, with little evidence, and instead seems to be promoting entirely speculative reasons for the rise with very little basis. In addition, one of the most likely explanations - the broadening of diagnostic criteria - is ignored entirely. But we know that widening diagnoses results in more identified cases of disease, by definition! When the American Heart Association changed the guideline for diagnosing high blood pressure in 2017, the proportion of people with the condition jumped by 50% immediately.

The review also positions this “exponential” increase as too large to be consistent with the number of kids who identify as trans. But is it? The Cass review cites the Office for National Statistics in the UK as a source that ~0.9% of people aged 16-24 identify as transgender in the country in 2023. Meanwhile, in 2021, the national prevalence of any code of gender dysphoria for people aged 17-18 was about 0.4%. These numbers aren’t exactly comparable for a number of reasons, but certainly it seems that a relatively small proportion of people who identify as transgender in the UK are experiencing a clinically significant amount of gender dysphoria at the moment. Remember - the review is looking at proxies of trans identification, such as referrals and clinical codes. If these proxies are still showing a rate that is less than half the rate shown in surveys, is it really a surprising figure?

Ultimately, there has definitely been a big increase in the number of young people who identify as trans and are turning up at gender clinics. To an extent I do agree with the Cass review - it’s hard to know the exact reasons for this. However, it’s clear that the review’s arguments about plausible reasons are unsound, particularly the error in discussing the “exponential” increase in cases. Indeed, by far the most likely explanation for more trans kids is simply that as a society we are much more accepting towards transgender people now than we were 20 years ago.

*Note: I’ve seen some discussion about the terminology here, but to avoid confusion I’m going to try and stick as simply as possible to referring to people assigned male at birth and identifying as girls as “trans girls” and those assigned female at birth and identifying as boys as “trans boys”.